As the sun sets over the Sudanese village of Al-Nuba, Ibrahim Abdelrahim rolls out carpets by the side of the Khartoum highway and his friends line them with plates of food.

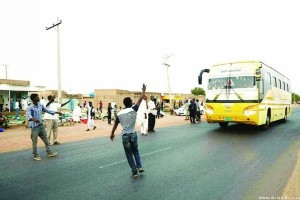

Minutes later, groups of villagers rush into the road, shouting and waving down approaching vehicles.

One brings a bus to a halt in the middle of the highway. Others join him and force the driver to park.

Sudanese men prepare food before an Iftar dinner by the side of the Khartoum highway in the village of al-Nuba Ramadan

Sudanese men prepare food before an Iftar dinner by the side of the Khartoum highway in the village of al-Nuba Ramadan ©Ebrahim Hamid (AFP)

“Please break your fast. It’s iftar time,” says a villager as dozens of passengers step out.

As the sky darkens, they settle down to plates of vegetables, meat and sorghum pancakes — a staple food in Sudan — along with cans of juice and water.

Just twenty minutes later, the travellers are back on the road.

Muslims across the world are marking the holy month of Ramadan, with the faithful abstaining from eating, drinking and sex from dawn to dusk.

Iftar — the evening fast-breaking meal — is usually a family event, but here in the Sudanese state of Jazeera it takes a different form.

Residents of villages along the 160 kilometre (100 mile) Khartoum-Wad Madani highway often compel travellers to pull up and join them for food by the side of the road.

“Holding collective iftar is an old tradition of our village,” said Abdelrahim, a doctor from Al-Nuba, 50 kilometres (30 miles) from the capital, Khartoum.

“When it’s iftar time, we try to stop all vehicles that pass through our village, and urge travellers to break their fast.”

Groups of men sit in rows as volunteers offer them food, while women break fast in separate groups nearby.

The volunteers who flag down passing traffic run the risk of serious injury as drivers attempt to avoid being stopped.

“They block the road and force cars and buses to park,” said a bus driver who was among those who stopped to break his fast.

“The passengers then get down, break their fast and later proceed with their journey.”

But for the people of the village, the tradition is a point of pride and a religious duty.

“People of Al-Nuba are famous for their hospitality,” Abdelrahim told AFP.

They believe it is their duty to stop those who are travelling through the village to have iftar, whether they want to stop or not.”

Muslims see Ramadan not just as a month of abstention but also a time for prayer, charity and the forgiveness of sins.

Offering food to travellers at this time is seen as a holy act.

The Prophet Mohammed reportedly told believers that someone who offers iftar to a fasting Muslim receives as many rewards in heaven as the guest receives for fasting.

Determined by the lunar hijri calender, Ramadan shifts back every year. The last time it was observed in early June was in 1983.

With nearly 16 hours of fasting from dawn to dusk and temperature hovering above 45 degrees Celsius, many travellers are keen to break fast as they pass through Al-Nuba.

“We are in Ramadan and it’s well known that people of Jazeera stop anyone who travels through their area during iftar time,” said Abdallah Adam, who broke his fast along with fellow passengers travelling to Medani, the capital of Jazeera.

Behind him, a group of travellers stood in rows offering prayers before eating the food laid out on several large green